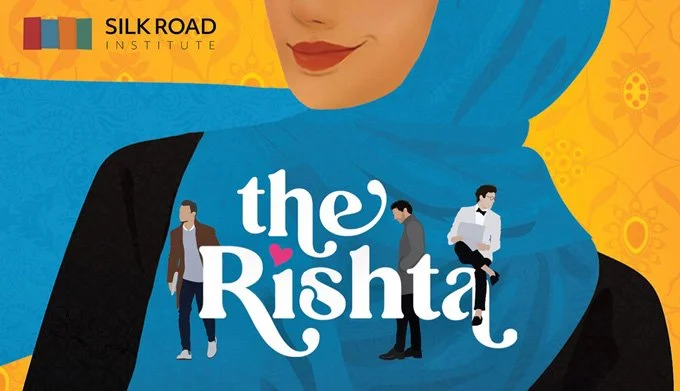

The Rishta - In(Spiring) Conversation with Uzma Jalaluddin

Photo courtesy of: www.uzmajalaluddin.com

"I live in the intersection of faith, culture and feminism."

I float Uzma Jalaluddin's quote back to her in our phone conversation, asking her to expand.

"Did I say that?" she asks with a laugh. "That sounds really good."

It does, and she did, when talking to the Toronto Star in 2018 on the future of feminism. That was the year she published her first novel, Ayesha At Last, the first romantic comedy about Muslim Canadians.

"My community was very open and accepting, and really happy to see that positive, hopeful, sweet, romantic representation in our community. So I felt -- I still feel a responsibility to make sure that I capture a really warm, authentic experience of Muslims. But I also know that I represent a certain kind of Muslim; my lived experience is different even from my own childrens'. As I've grown as an artist I've come to accept that, but I still feel -- as I think so many BIPOC creatives feel -- this limitation of 'Okay, I have to make sure that I'm still thinking of the community sharing their story as a creator'."

As a wife and mother, a public high school teacher for over 20 years, a bestselling novelist, and now the first commissioned playwright for Silk Road Theatre, Uzma wears her many hats with grace.

"Being an artist alone in your room all day creating is wonderful, but also getting out there and talking to people, interacting with them really grabs you in a way that I don't think anything else does."

Uzma was already an established storyteller when Silk Road came knocking. Started in Montreal in 2018, Silk Road holds the prestige of being North America's first professional theatre company dedicated to the telling of Muslim stories. In fact, showtimes right now are all at 830 PM to accommodate those fasting for Ramadan, a small step for scheduling, a huge impact for the community.

Guesting on Episode 7 of The Story So Far, Silk Road Institute's podcast, Uzma talked about how Muslim stories are all too often told through the lens of struggle, of otherness. Hearing that, I understood how stories are so often valued according to how bloodied and tear soaked they are, how so much weight is given to the tales in which surviving is the victory. Which is exactly why Uzma writes about the happier parts of life within her community.

The piece she wrote for Silk Road, The Rishta (The Suitor, in Hindi) is a perfect example. It's a playful romance wherein the witty heroine manipulates cultural traditions in order to marry the man she loves. When Samah, a young South Asian woman, falls in love with a Moroccan man named Hussain, she's sure her parents won't approve of the intercultural relationship. With the help of a matchmaker, Samah presents intentionally terrible "suitors", so that the one true suitor, the man she loves, is the only option.

"[Samah] takes the tropes of arranged marriage -- which are so often misunderstood in Western society -- and flips it on its head and uses it as a way to empower herself. And I think that's one of the hidden messages of The Rishta: there is no rishta, she uses it to get what she wants. Her parents don't even want her to have a rishta. So this isn't really about an arranged marriage, it's about subverting the ideas of arranged marriage."

A chorus is provided by the deceased grandmothers, which resonates with me, and I wonder if this is associated with various "old worlds". As a second generation Canadian, my maternal grandmother's opinion loomed large in my family, even when she was wrong. She had weird habits and an occasionally prickly temperament, but she also had a Devil may care attitude, and a big picture scope that were unparalleled.

"I like the idea of having input from multiple sources. South Asian families, like so many families, are complicated. I like the idea that the characters on earth are getting into all this trouble -- this isn't a Muslim idea at all, by the way, our spirituality doesn't look like this -- but I like the idea of grandmothers watching with disapproval the events that their children are making."

It also provides a layer to the story: the audience is watching the players and the grandmothers, the grandmothers are watching the players, while the players can only see themselves.

So how does a novelist become a playwright? I'd venture that it takes a fair amount of courage and thirst for exploration, but a supportive team sure does help.

"When Silk Road first approached me in 2019 to write a play it was interesting because I hadn't written any other books, I had just published my first; and they were like 'no, we want something funny. We want something that parents can bring their kids to like a fancy outing'. I commend them for being so ambitious and doing things very professionally. This wasn't done in a basement with the Auntie and the Uncle acting out all the parts. They were very ambitious in their scope, and that really attracted me to them. We kind of learned together. I am their first commissioned playwright, and I was very up front that I don't know this world, but I'm very excited and eager to learn. They hooked me up with some great dramaturges, like Debra Forde, and I also worked with Playwrights [Workshop] Montreal's Sarah Elkashef. Both of them were really instrumental in helping me to put the story on the page. Silk Road really championed it. I feel like the work they're doing is so important. We're a young community -- the Muslim community in Canada is very young, and we're majority made up of first and second, maybe third generation immigrants, though some have been here longer. So it's time for us to really have an opportunity and a say in building the culture around us. Not only through becoming doctors and lawyers and engineers, but also through art."

Motherhood itself is part of what sparked Uzma's literary career. In the Silk Road episode she talked about the sense of "now or never" that came to her at the time. That was some time ago now, the distance easily marked by her growing children, as parents will understand. One of her sons has already read her novel and enjoyed it. I ask her how that impacts her sense of legacy, and that's something she considers on a grand scale.

"My first novel was optioned by a major Hollywood producer. My second book was also optioned by another Hollywood producer. And those are the types of things that I think that the people who are coming up behind me, young people who are looking for a book or story about people who look like them, might see as an inspiration, like 'oh! This is something I can actually do'. When I had that 'now or never', I had my second child, and I thought this is a dream of mine that I've always wanted to do. I'm lucky in a way because I have a very supportive spouse who also believes in me. So I might as well take the time and the opportunity to try to do it, knowing that it won't happen overnight. That baby that made me think about taking that leap into writing is now 15 years old. It's not a quick journey, you know, it's a marathon. But the idea that these books will mean stories might inspire others to follow in my footsteps, that's really what makes me happy."

Her first play, a run at The Centaur, it's a great start to a year destined to be filled with roses for Uzma. Her next novel, Much Ado About Nada drops in June, and in October Three Holidays and a Wedding will be on shelves, a novel she co-wrote with fellow Torontonian Marissa Stapley. I'll be keeping my eyes on Hollywood to see which of Uzma's stories make the big screen (because they are destined to). I'll also be keeping my eyes on Silk Road as they pioneer Muslim art in Montreal, and across the continent.

WHERE: Centaur Theatre, 453 Saint Francois Xavier St, Montreal, H2Y 2T2

WHEN: On now, through April 8

TICKETS: Centaur Theatre

METRO: Place - d'Armes