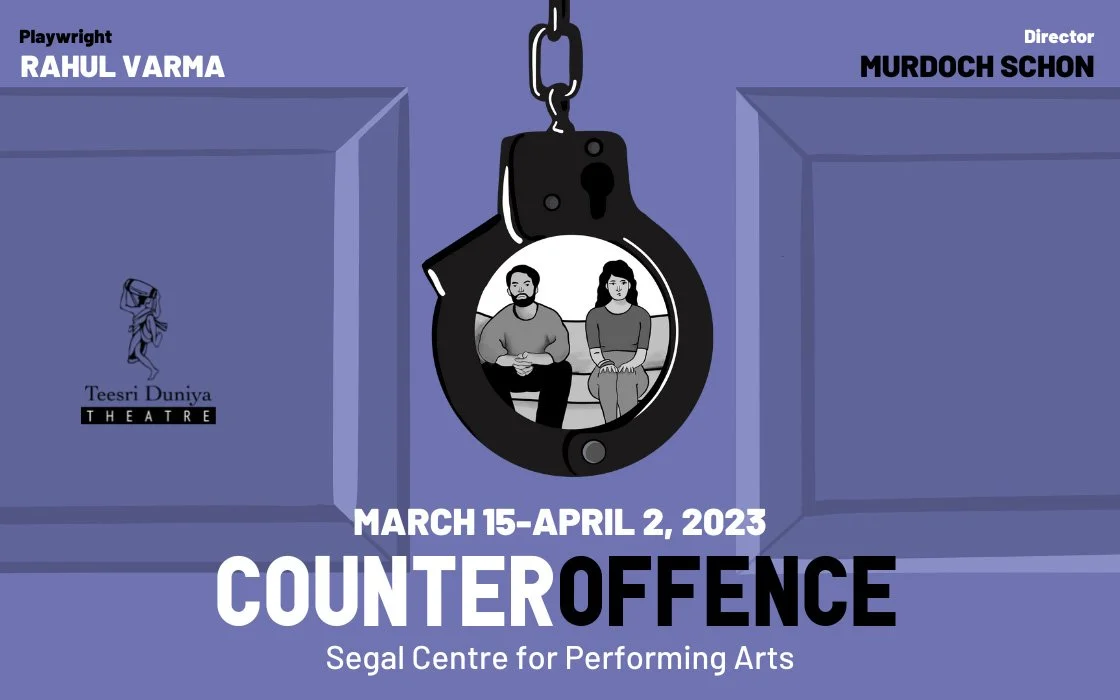

Counter Offence - A Review

Trigger Warning: Counter Offence, and so this review, contains themes of domestic violence, racism and police brutality.

A. Sharma, AJ Richardson (photo by Brooklyn Melnyk)

When I was asked to write a review for Counter Offense, I was hesitant. Being an Iranian Canadian, and a survivor of domestic abuse, I knew the play would take me on a convoluted and emotional journey. So naturally I invited an emotional support friend to join me. He's born to Iranian Indian parents and a cinematographer, and we planned to discuss the play while comparing notes after. More on that later.

Counter Offense was originally written in 1995, right after the Quebec referendum. The play ran for two nights in front of an audience in March 2020 before being shut down due to the pandemic. It is back again after three years with a whole new cast and crew. The playwright, Rahul Varma, welcomed us in Urdu, and then gave a powerful land acknowledgement, situating us in the current day occupied indigenous land, and inviting us to challenge and dismantle the oppressive systems we currently live and participate in. This was humbling, as I took a moment to reflect on my own life’s journey, and where on the continuum of power and privilege I stand.

I hate spoiler alerts, so I will try to keep the plot a mystery. But much like Chronicles of a Death Foretold by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, the play starts with the discovery of a dead body, and a time travel plot device between parallel stories that help us unravel the mystery of a murder. The main characters are Shazia and Shapoor, a young wife and husband. Shazia (she/her) is from a muslim indian family, and Shapoor (he/him) is an Iranian exchange student who doesn’t have an immigration status, and is thus legally bound to Shazia in more ways than one. The two are caught between the desire to please their parents, their cultural upbringing, and their toxic love for one another. But all promises of a future are shattered when Shapoor physically abuses Shazia in a rage, and betrays her trust. With the support and counsel of her social worker, she decides to leave Shapoor and files for divorce. Given his status, Shapoor loses his rights of staying in Canada.

Moving on from an abusive relationship is never easy, and in this play, Shazia portrayed the reality of women in certain cultures, and the weight of their parents’ shame, projections, and expectations. Add to that the enormous responsibility of sponsoring an ex-spouse through their migratory path. Misogyny and sexism are taught to women from a young age, and mostly by those who say they love us the most. This was the case with Shazia’s family, who couldn’t stand the thought of her suffering and being in an abusive relationship, but simultaneously kept giving her mixed messages about the horrors of being a divorcée that no one will ever marry again. Just some examples of why certain women will choose to stay. The play did an excellent job of showing the harrowing dissonance that follows domestic violence.

O. Price, S-T. Stone-Richards (photo Brooklyn Melnyk)

In a conversation with the playwright during the meet and greet, Verma said something to my friend and I, and I hope I am paraphrasing it correctly because that phrase sent chills down my spine: this script explores the continuum of those who have no freedom, and those who have the freedom of power.

That freedom of power he was referring to was really an abuse of power, and a sense of righteousness - of entitlement. This was the case with the husband who beat his wife into agreement with him. It was also put on display through the use of gratuitous racist slurs, and acts of verbal violence and cruelty directed at Shapoor, and in anecdotal dialogue directed at the audience. It almost felt caricatural and like the most obvious form of racism - the kind you would find if you looked it up in the dictionary in 1995. Someone who has never been on the receiving end of a racial slur may watch this play and think to themselves that we as a society do not talk like this anymore, that we do not stand for this kind of language and behaviour. That we know better now. But there is racism in body language, in microaggressions, in our emotional charge and in our reaction. And in 2023, we’ve gotten to the point where we can identify and name the invisible and silent cues of racial imbalance.

Remember my emotional support friend who came with me to the play? At the end of the play, the lights had barely come back on, and having watched a pretty heavy play from a trauma informed lens, we were both gathering our thoughts to go compare notes. I was still fighting back tears from the abuse scene, and also wanted to check in on my friend and his feelings. I knew he had been taking notes because he had turned his phone screen to black, covering it with his non-typing hand, and was writing bullet points during key moments. When we were getting up to leave, he turned to talk to me and his coat touched the woman next to us, for which he immediately apologized. She didn’t accept his apology. Instead, she told him he was “rude the entire play, being on his phone, dropping his stuff (he dropped his water bottle by accident), and now had hit her with his jacket”. Like I said, the lights had barely come on, and this person took the first opportunity that presented itself to have an emotionally charged reaction, and to tell my friend how to behave in a theater, lest he cause any disturbances or make her the least bit upset.

Counter Offense wanted the audience to reflect on power dynamics, and to use art to lead the charge on systemic change. But I’m not sure everyone walked away thinking about their role and responsibility in making the world a more inclusive and accepting place. Or at least, I doubt the person next to us picked up that message. So if you want to watch a play, or are in a crowded metro, or in a meeting at work, or in a group of friends, make sure to pay attention to how you react to the people around you. Notice if there are any differences in the emotional load you are projecting. Ask yourself: Does this person annoy me for reasons that really matter*?

*A question asked to the audience at the end of a The Likeability Dilemma for Women Leaders, TedX talk by Robin Hauser, Director of documentary films. It applies here as well.

WHERE: Segal Centre, 5170 Chem. de la Côte-Sainte-Catherine, Montréal, QC H3W 1M7

WHEN: March 15 to April 2, 2023

TICKETS: Teesri Duniya Theatre